Supercar Rewind: The Mercedes-Benz C-111

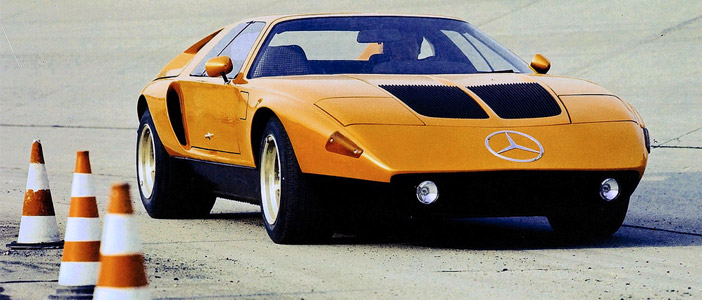

Let’s take a trip back to the 1970’s and have a look at Mercedes-Benz’s ultimate experimental super car of that decadent decade. The compact wedge in bright orange, a shade internally called “weissherbst”, expressed power, elegance and speed. C 111 was the designation of the futuristic study displayed by Mercedes-Benz in September 1969 at the Frankfurt International Motor Show (IAA). The car broke new ground in terms of both engineering and design. Motor show visitors crowded around the sports car, marveling at its intriguing – as well as polarizing – design. Was this the worthy successor to the famous 300 SL Gullwing? The car’s style, dynamic lines and classic gullwing doors promised just that to lovers of refined cars with the three-pointed star on the hood. This happened 35 years ago, at the C 111’s presentation in Frankfurt. In the spring of 1970, an even more elegantly clad C 111-II made its appearance at the Geneva Motor Show, prompting interested parties to send blank checks to Stuttgart to secure one of these cars for themselves.

However, it had never been planned to produce the new Gullwing in series, and the C 111 was not to appear in showrooms. The coupe may have looked like the systematic further development of the Sport Light models from the 1950s, but it was not a design study for a new SL: it was to serve as an experimental car. Laboratory machines as beautiful as this Mercedes-Benz, designed among other things to test glass-fiber-reinforced plastics as bodywork material, were – and still are – few and far between, however. The coupe’s lightweight skin, opening up new possibilities in the aerodynamic design of sports cars, was bonded to a steel frame/floor unit.

Powered by a Wankel engine

The second revolutionary feature of the C 111 was hidden under its skin. The first experimental car of 1969 was powered not by a reciprocating-piston engine but by a Wankel – or rotary-piston – engine. At the time, many manufacturers were interested in Felix Wankel’s unconventional propulsion system. Mercedes-Benz, too, had been experimenting with Wankel engines – KP through to KC series – since 1962. However, the Wankel engine was to be extensively road-tested before being fitted in production cars. The last Mercedes with a rotary-piston engine from this series was the four-rotor DB M950 KE409 of the C 111-II in 1970.

The performance of the C 111 even with the three-rotor engine was convincing right from the start. In 1969, the Wankel engine developed 280 hp from 600 cubic centimeters of chamber volume per rotary piston and gave the car a top speed of 260 km/h; with this engine, the car accelerated from standstill to 100 km/h in five seconds. The C 111-II of 1970 was powered by a large four-rotor Wankel engine which developed 350 hp and gave the car a top speed of 300 km/h. The second C 111 accelerated from standstill to 100 km/h in highly respectable 4.8 seconds. While some of the engines in the C 111-I cars had still featured dual ignition which was difficult to adjust, the four-rotor engine was equipped with single ignition exclusively. Both engines were direct-injection units.

The development department of Mercedes-Benz eventually succeeded in solving the engineering-design problems involved in the rotary-piston principle, especially in engine mechanics, but the problem of the Wankel engine’s poor degree of efficiency, due to the elongated, variable combustion chambers of the rotary-piston principle, was not to be overcome with technical modifications. This problem was simply inherent in the design: in a Wankel engine, the fuel burns within the space between the convex side of the rotary piston and the concave wall of the piston housing rather than the cylindrical combustion chamber of a reciprocating-piston engine. The variable, anything but compact combustion chambers of the Wankel engine were responsible for poor thermodynamic fuel economy as compared to a reciprocating-piston engine, resulting in significantly higher fuel consumption for the same output. The engines of the first two C 111 versions were straightforward gas-guzzlers. And since the pollutant content in the exhaust gas of the Wankel engines was also too high, Mercedes-Benz discontinued work on this type of engine in 1971, in spite of its impressively smooth running characteristics and compact size.

In retrospect, Dr. Kurt Oblsnder, head of engine testing in the C 111 project, described the Wankel engine as follows: “Our four-rotor engine with gasoline injection represented the optimum of what could be reached with this engine concept. The multi-rotor design called for peripheral ports for the intake-air and exhaust-gas ducts. We were able to solve the difficult problems in engine cooling and engine mechanics by technical means. But the main problem of the concept, its low thermodynamic degree of efficiency, remained. Due to the elongated, not exactly compact combustion chambers, fuel economy was poor, resulting in high fuel consumption and unacceptably high pollutant emissions. These drawbacks were inherent in the design principle.”